Paying the price

Despite cultural concerns, Native women help change the face of medicine

By Candace Begody

Special to the Times

TUCSON, Ariz., March 19, 2009

(Special to the Times - Candace Begody)

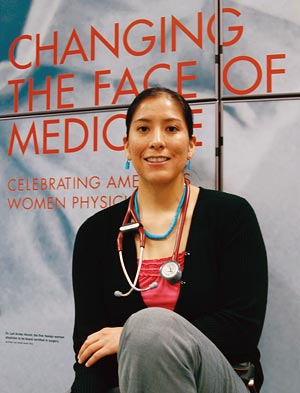

Naomi Young, of Sawmill, Ariz., a fourth year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, poses in front of the "Changing the Face of Medicine: Celebrating America's Women Physicians" exhibit. The exhibit is on display at the Arizona Health Sciences Library in Tucson until March 27.

T he first time Naomi Young met the women who changed medicine, she began to contemplate applying to medical school - a dream she'd had since she was a little girl growing up in Sawmill, Ariz.

Fours years later, Young is in her fourth year at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and is one year away from becoming a doctor.

And as for the women who inspired her, their faces are part of a traveling exhibit called "Changing the Face of Medicine: Celebrating America's Women Physicians," sponsored by the National Library of Medicine.

"The first time I saw it, it was like a steering force for me to apply for medical school," Young said of the exhibit, which she recently saw again, "and fast forward a couple of years, it's like clarification that this is the right path for me."

The exhibit, which will appear in 61 libraries nationwide by the time it closes in 2010, is housed in the Arizona Health Sciences Library, its only stop in Arizona, until March 27.

The exhibit features two Native American women including Susan La Flesche Picotte, who was born on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska and in 1889 became the first Native American to earn a medical degree.

An online exhibit that features 29 Native women in medicine, including six Navajos, supplements the traveling exhibit.

The Navajos are:

- Lori Arviso Alvord, the first Navajo woman to be certified in surgery;

- Patricia Nez Henderson, the first Native woman to graduate from the Yale University School of Medicine;

- Mary H. Roessel, the first female Navajo psychiatrist to provide IHS clinical care in New Mexico;

- Bernadette T. Freeland-Hyde, a pediatrician who has devoted a decade to improving health care for children of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community;

- Melvina L. McCabe, director of geriatrics in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine; and

- Kathryn Ann Morsea, medical officer at the Gallup Indian Medical Center.

"I'm very humbled and honored," said Nez Henderson by phone from her home in Rapid City, S.D., of being featured in the exhibit. "There were times when I would sit by a Native American jewelry store contemplating leaving and it was definitely worth it."

Nez Henderson, originally from Teesto, Ariz., said it became evident that Yale did not have any experience working with Native American students and the Native students who were there seemed to have little knowledge of their culture, traditions and language.

"There was very little support for Native students," she said. "Now, I tell students that if they really want it, they have to want it from the heart because the head will want to quit, but the heart has to be the one that drives you."

Natives underrepresented

Since the first Native American woman received her medical degree, the number has been increasing, according to Yvette Roubideaux, Rosebud Sioux, an assistant professor in the UA colleges of Public Health and Medicine.

Roubideaux, who is also featured in the online exhibit, said that despite the increase, Native Americans still constitute the most underrepresented group in the profession.

Across the country, there are over 200 members in the Association of American Indian Physicians.

At the UA today, there are about 11 Native American medical students - a change from one to two in each class 10 years ago.

Roubideaux said Native women have brought a different perspective to the medical world.

"We bring an important, diverse voice to the general field of medicine," she said, "to help people understand that taking care of American Indian patients, it's not one size fits all.

"We are a part of the Native community," Roubideaux added. "We are proud of our heritage, and we bring our history, our tradition and background so we can help teach other people how to best treat Native American patients."

Along with the online and traveling exhibits, portraits of Native American physicians with ties to the UA were also debuted.

"Many believe that if they want to become a physician they have to give up their Native identity," Roubideaux said. "But this exhibit lets students know that they can still be a doctor and still retain their pride in being Native American."

About 25 portraits of Native physicians, all taken by Tucson photographer Michael Stoklos, have been mounted in the library. Many are dressed in traditional regalia. Stoklos, who is non-Native, donates money to support Native medical students at the UA.

"We wanted to help American Indian students see that there are other American Indian physicians who have achieved this goal and to let them know it's possible," Roubideaux said. "A lot have become nurses thinking it was as far as they could go."

Protection prayer

Like many before her, Young thought about giving up.

In anatomy class, for instance, Young spent most of her free time in the lab with up to 60 dead bodies, just to prepare for the next class.

"There's just so much detail you have to know," she said. "As soon as the class was over and I took my final, I was having a (protection) prayer at Grandmother's house."

Young, who is Táchii'nii (Red Running into Water clan), born for Tábaahá (Edge Water clan), is not the only one undergoing ceremonies. The Association of Native American Medical Students at UA and Stoklos bring in traditional healers to bless the labs and students.

"At one point we had to hurt animals - like breaking the legs of a dog - and then we had to fix it," Young said. "I had to constantly go home and get prayers done."

During "trauma call," in which Young was on call for 24 hours, she saw bike accidents, gunshot wounds, stab wounds and lost patients on the examining table.

"Death was coming in through the door," she said. "It's like a trade off, sometimes you have to lose some and some you can save."

Young still prays to let go of the haunting past - when a woman involved in a three-car pileup died on the table.

"That was the first time I had witnessed something like that," she said. "You have to let it go and you can't hold those thoughts upon the next patient."

Many, like Young, struggle to keep a spiritual balance but in the end, the struggle is worth it, Roubideaux said.

"The students go to a medicine man to make things all right for them," she said, "because it means that a student can get through med school, eventually practice medicine in their communities and work with the healers. It's a small price to pay."

Many of those featured in the exhibit have had similar experiences, she added. "These physicians are proud of their heritage and were able to walk well in two worlds."

"Changing the Face of Medicine: Celebrating America's Women Physicians" will be on display at the University of New Mexico's Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center starting April 10 through May 20.

The exhibit was made possible with support from the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health and the American Medical Women's Association. The online exhibit can be viewed at www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine/.